5 Reasons Why Benedictine Spirituality Stands the Test of Time

Reports show that Church attendance in the United States continues to decrease. More young people claim no religious affiliation, and others give the impression that, as a society, we are too sophisticated or advanced for faith in God. The Church’s efforts to evangelize focus on how to address our post-Christian world. Without minimizing any of the challenges the Church faces in today’s culture, I am encouraged to see young people hungering for the truth and desiring holiness.

Based on my experiences with the young men I communicate with regularly who express interest in monastic life and look to Conception Abbey as a place of prayer and peace, I’m convinced that Benedictine spirituality has much to offer our world today. The Benedictine way of life is not drastically different from the Christian life, but is rather a specific, intentional way of living out the Gospel message and responding to the invitation to follow Jesus. I offer five reasons why I believe Benedictine spirituality is attractive in today’s world.

The Search for God

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus says the kingdom of heaven is “like a treasure buried in a field, which a person finds and hides again, and out of joy goes and sells all that he has and buys that field” (13:44). God is always searching for us, prompting us to draw nearer by His grace, and even going insofar as to send us His only begotten Son to redeem humanity and draw us to Himself. God seeks us first, but we are also called to respond to this grace. Our search for God is like a path of discovery. Cardinal Basil Hume asked, “What, then, is at the center of our monastic calling? An exploration into the mystery which is God. A search for an experience of His reality. That is why we become monks. The exploration is a life-long enterprise” (Searching for God, p. 28). Essential to this “exploration” is a heart that is open to listening and looking for God in all aspects of life.

It is clear that in today’s ever-changing world, many people are searching for what will bring peace and lasting happiness. This search has introduced many false paths and spiritualities that lead us away from the truth of Jesus Christ. In the parable cited above, the person is searching for a treasure, and it is found, he is willing to make the sacrifices necessary to have it because it brings about real and lasting joy. Similarly, the Benedictine search for God is lifelong; it’s a path marked with struggles and joys. Ultimately, though, it is a path that leads to God, our true treasure. St. Benedict indicated what perseverance on this path looks like: “As we progress in this way of life and in faith, we shall run on the path of God’s commandments, our hearts overflowing with the inexpressible delight of love” (Rule of St. Benedict, Prologue, 49). While we can experience God’s presence through the many good and beautiful things of this world, the only path that leads to lasting peace and happiness is found in seeking God. Many young people today find themselves turning back to faith in God and the truth and beauty found in the Catholic Church because they have fallen victim to the empty promises and seductions of the world. The search for God becomes a journey with purpose, meaning, and an authentic understanding of who we are and who God is. Benedictine spirituality encourages this search and sets us firmly on that path.

Silence

Pope Francis composed a prayer to the Blessed Virgin Mary, which included this petition: “Open our ears; grant us to know how to listen to the word of your Son, Jesus, among the thousands of words of this world.” We are all hyper-aware of the thousands of words and voices bombarding us at any given moment—noise that comes from the radio, the internet, and conversations taking place all around us. All of those words, along with countless other distractions and demands, compete for our time and attention.

In our search for God, silence remains a necessary instrument, which is why silence takes an important role in a monk’s daily life. St. Benedict wrote, “Speaking and teaching are the master’s task; the disciple is to be silent and listen” (RB 6:8). Silence is the environment that allows us to properly listen to God’s voice and to those around us. While we can find silence uncomfortable or awkward, it can also challenge us to listen to the God who dwells within and speaks in the depth of our heart. Author Fr. Michael Casey has reflected, “There are some who fear silence, as children fear the dark. Once their thoughts are no longer prompted externally, deeper thoughts may surface and they are afraid of the result of that unaccustomed process. So they attempt to frighten away the ghost with noise: clatter, conversation, and the cheerful inanities of media entertainment” (Sacred Reading, p. 94). I have seen several vocation candidates and retreatants go through a process of “noise-detox” when first arriving at Conception. Our guests seem to require at least a day of silence and away from their smartphone before the “inner noise” fades away. But, when they can avoid the unnecessary noise in their lives, they learn what centuries of monks have discovered—namely, how to cultivate inner silence, which is the ideal setting for prayer. While the time alone with God is initially scary, we come to a greater sense of inner peace, which is very freeing and lifegiving. Benedictine monasteries are havens for the kind of silence that trains a person to listen to God’s gentle whisper (cf. 1 Kings 19:11-13).

Complete silence at all times is not a realistic possibility (or goal) for the Benedictine monk, but young people can learn to appreciate a temporary escape from the superficialities and noises of the world in exchange for the gift of deep and lasting peace that comes from prayer and listening to God’s voice. The Benedictine way of life provides training so that our hearts and minds become more attuned to God.

Community Life

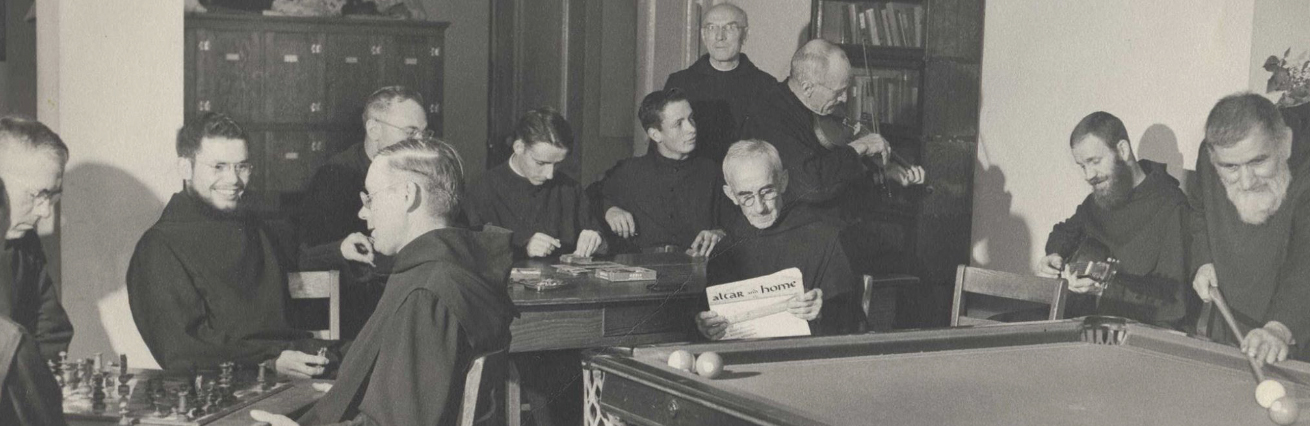

I have encountered many people who desire to live their Catholic values more faithfully but lack the support from others and the strength to do so. It is true that we can experience community by grouping together and connecting with like-minded individuals on the internet or social media—and this may serve as a temporary reprieve, but it’s hardly a long-term substitute for authentic community and face-to-face interactions. Community for the Benedictine addresses the strong desire to cut through the superficial and truly be known by others. In monastic life, we come to know each other very well, weaknesses and all. When seeking God in community, we discover the joy it is to experience the support that comes from sharing with others the same hopes and way of life.

The image of community life in a Benedictine monastery might appear perfect and ideal all the time, but this is hardly the case. Difficulties and conflicts arise in community life, but there is much we can learn from them. Cardinal Basil Hume reminded novices, “Difficulties are the voice of God speaking to us. God speaks to us through events, through circumstances. And when these are hard to bear He is trying to make us less reliant upon ourselves, teaching us to have more confidence in Him” (Searching for God, p. 80). While disagreements and differences in personality can easily become a source of frustration, they also provide an opportunity for us to come to accept one another and make sacrifices to strengthen our charity. Monks support and encourage one another in times of difficulty, and celebrate with one another during joyful times. St. Benedict instructed, “No one is to pursue what he judges better for himself, but instead, what he judges better for someone else. To their fellow monks they show the pure love of brothers” (RB 72:7-8).

In our world of individualism and self-preoccupation, I find that young people want a deep sense of belonging and communion with one another. From the outset of His ministry, Jesus surrounded Himself with a core group of disciples, thus teaching us that the spiritual life is always a journey that we undertake with others. St. Benedict continued this pattern with monks living not alone, but gathered together for the sake of a common mission and goal. He strongly encouraged fraternal charity and rebuked anything contrary to it, like the evil of murmuring (or gossip) (cf. RB 6:8). Many characteristics describe a good monk, but towards the end of his Holy Rule, St. Benedict emphasized the respect and mutual charity for one another as the hallmark of the faithful monk. We do not always see eye to eye with one another, but the fact that we live in close quarters and pray, work, eat, and recreate daily with one another challenges us to overcome petty disputes and seek reconciliation. Many people in the world are quick to lose their temper, but Benedictines proclaim the value of bearing patiently with one another. Growth in holiness comes from giving ourselves to God in a particular way of life, in a particular community, with particular people. We might want to escape from these particular circumstances, but it is a far greater test of our virtue to forgive rather than ignore, or to show charity rather than to allow our wrath to blaze. God uses community life to be one of the greatest blessings and the surest way of addressing the areas in our heart that still need to be purified.

Order

Everyone has the same amount of time to spend each day. We have the time, but the struggle is deciding what really matters in life and how we should spend this precious time. We make time for what we regard as important. The monks gather multiple times a day to pray because we regard it as important. Sometimes it is challenging to stop in the middle of another activity in order to make time for God, but we follow the counsel of St. Benedict, who said, “Nothing is to be preferred to the Work of God” (RB 43:3).

In the creation account, “the earth was without form or shape, with darkness over the abyss and a mighty wind sweeping over the waters” (Genesis 1:2). Prior to creating any living thing, God arranged the days, and thus brought order from the chaos. One significant obstacle for spiritual growth today is that many people’s lives are in chaos rather than order. Many people struggle to find order amidst the chaos because they find themselves pulled in multiple directions and their good intention to pray is quickly supplanted by other immediate and unexpected demands. For the monk, life is intentionally organized a little more simply: the bell rings, and together we go to pray. While the monk still has to confront the inner reluctance to pray that all people experience, his time for prayer is built into the day and all other activities are scheduled around it.

A great aid to bringing order to our spiritual life is establishing a “Rule” or “Plan of Life.” St. Benedict wrote a Rule for his monks to follow, and the monks are not to “deviate from it” (RB 3:7). People falter in their spiritual lives because they do not keep to their plan, which can quickly devolve into aimlessness and wandering without a purpose. A rule provides a schedule of the occupations and practices of devotion a person desires to perform during the day. The advantage of some kind of plan or schedule is that it gives a constancy and regularity to one’s efforts toward greater perfection in Christ. St. Josemaría Escrivá wrote, “Without a plan of life you will never have order” (The Way, 76). It’s often the case that without a schedule, we can waste time, become indecisive, neglect our duties, or become lax in our resolutions. When we fail in doing what we had originally set out to do, discouragement can easily take hold in our heart. But, if we have found order through a fixed schedule of life, there is much less danger of losing time and being caught unprepared by some unexpected event. Ordering our life keeps us on a path where we are far more likely to keep to the spiritual practices necessary for spiritual advancement.

Benedictine life provides people with a predictable structure to the day and a rhythm that allows them to offer praise and thanksgiving to God. The primary “vehicle” through which we monks turn to God is by praying the Psalms, which give voice and expression to our inner experience, or that of the Church and the world. In remaining disciplined to a schedule, we protect ourselves from being overrun and sidetracked by the countless demands of our time and attention. Instead of finding the schedule stifling or confining, when monks embrace it, the path can lead us to great freedom and peace of heart. St. Benedict encouraged his monks: “Do not be daunted immediately by fear and run away from the road that leads to salvation. It is bound to be narrow at the outset” (RB Prol., 48).

Reverence

St. Benedict mentions throughout his Rule the importance of reverence in prayer: “Let all the monks rise from their seats in honor and reverence for the Holy Trinity” (RB 9:7). The times we gather in church for praying the Psalms are expressions of this reverence for God who is the source of all gifts. Sadly, we see many expressions in our world today where there is a lack of reverence, or sometimes an utter disregard for God and holy things. Lack of reverence denies the transcendent and keeps us focused on ourselves. To be humble is to recognize that we are creatures, and God is the Creator who provides all things for us. Monasteries are places where God is praised and glorified. As we celebrate our 150th anniversary, it is powerful to recognize that monks have been interceding daily on behalf of the Church and the world. This has had a spiritual impact that truly cannot be measured, but that we believe in faith has been significant in the lives of countless individuals, monks and non-monks alike.

Life itself is a good—whether we are talking about the unborn child in the womb, the poor and the destitute, or the elderly, and each human person is endowed with innate dignity. Christ dwells in other people, and monks are reminded to see Christ in one another, especially in the sick and in the guest who comes to the monastery (cf. RB 36:1; 53:1). I have always found that the meeting of reverence for God and neighbor comes together when the monks process into choir for the Divine Office, two-by-two, bow to the altar (which represents Christ), then turn and bow to one another acknowledging Christ’s presence in the other as well.

Monks seek to relate to God and one another with respect, but also to the rest of creation. St. Benedict advised the monastery cellarer to “regard all utensils and goods of the monastery as sacred vessels of the altar, aware that nothing is to be neglected” (RB 31:11). We are invited to be responsible stewards of the many tools entrusted to us. Living out of responsibility rather than carelessness shapes our hearts to be grateful and more aware that everything we have is a gift received from a Loving Father in Heaven. It also reminds us that our ultimate end is union with God, so that all our efforts are directed to Him. Jean-Pierre de Caussade, stated it well: “There is only one secret of seeking holiness—make use of whatever God offers you, for everything can lead you to union with Him” (Abandonment to Divine Providence).

— Fr. Paul Sheller, OSB

Abbey Vocation Director

Posted in General, Monastery News